|

p.8-9 Chess Perception

Chess cognition is mostly unconscious. In studying a position,

a master may quickly understand that there are three viable possibilities for the player on move. But how his brain has determined

this, he has no idea. And even when he is deliberating among the viable options, there is typically little inner dialogue.

Chess thinking is rarely linguistic.xiv Also, chess cognition bears little or no resemblance to computer number-crunching.

Contrary to popular belief, great chess players usually don’t think many moves ahead,xv and judgment is more

important than calculation.

Chess provides a striking example of how knowledge can influence

perception. When a novice and a master look at a position, there is a profound difference in their experience. The master

sees the power of the pieces:

he immediately knows which squares the bishop attacks; no conscious

thought is required. More complicated matters can also be perceptual. A master can immediately perceive that a square is weak,

a bishop is bad, a pawn is backward, and a queen is pinned. He can perceive all this in one or two seconds of scanning the

board, while the novice has only taken in the fact that there is chess being played on the board rather than checkers.

p.11 Changes in chess perception are typically gradual. Sometimes,

however, you can experience rapid shifts. In the last round of the 1987 U.S. Open, I accepted an early draw offer from Grandmaster

Lev Alburt. The position was dead equal, we were about to swap some pieces, and I did not expect to beat my famous opponent.xxiv

Afterwards, when I looked at the final position with my trainer, Boris Kogan, Boris said, "Of course you are a little

worse here." "Why?" I asked. "Because your b-pawn is weak." "No, it isn’t." So we played it out. Twenty moves later,

Boris had captured my b-pawn with his knight, and I was sure to lose. So we played it out again, and the same thing happened

(except this time, he captured my pawn with his king). Boris had convinced

me he was right, but more amazingly, he had changed my perception of the position. The black pawn now looked weak to me. I could now see what Boris had seen. [footnote 24] The

game should continue 14…axb5 15.Rxa8 Bxa8 16.dxc5 and then black can recapture the pawn in either of two ways."

[JLJ - Rybka evaluates the final position of the game in question

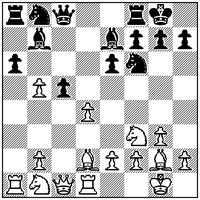

White: Alburt Black: Rachels

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 e6 3.g3 d5 4.Bg2 Be7 5.O-O O-O 6.c4 dxc4 7.Qc2

a6 8.Qxc4 b5 9.Qc2 Bb7 10.Bd2 Be4 11.Qc1 Bb7 12.Rd1 Qc8 13.a4 c5 14.axb5 1/2-1/2

| Stuart Rachels |

|

| Lev Alburt, position after 14.axb5 |

as +0.10/21 (tiny advantage to Alburt) after the required recapture 14...axb5]

p.12 ...if you know only a little bit about chess, looking at a game can be downright irritating, because you’re

frustrated by your partial understanding, and because you realize that, to understand more, you’d have to do something

tedious: you’d have to figure out where all the pieces on the board can move to, in each position. And even if you do

that, you may grasp a few particulars about the position, but the position as a whole will get lost like a forest for the

trees, and the game will be a blur.

p.17 What

is chess, if not a sport? Chess is a strategy game. It is also, I believe, an art. Chess compositions are artistic creations

in the fullest sense of the term. However, you might think that calling a chess game

a work of art is dubious. Chess games are more about winning than creating;

chess is a battle that resembles war more than painting. Yet this is a false dichotomy. A battle can produce objects of aesthetic value.xl Chess is a game, an art, and a competitive struggle.

That is nothing to be ashamed of, is it?

After 14...axb5 15.Rxa8 Bxa8 16.dxc5 Bxc5 17.Be3 Bxe3 18.Qxe3 Nbd7

(24-ply) Rybka2.3.2a

1. (0.15): 19.Qd4 Bc6 20.Nc3 Qb7 21.Qb4 Nb6 22.Ne1 Nbd5 23.Qd6 Rc8 24.Nxd5 Bxd5 25.Bxd5 Nxd5

2. (0.14): 19.Rc1 Qa6 20.Ne1 Bxg2 21.Kxg2 Rc8 22.Rxc8+ Qxc8 23.Na3 Nd5 24.Qd3 b4 25.Nac2 Qc5

|